There is something curious about the relationship between monarchies, national identities, and the passage of time. Even if you know that monarchies have systematically sought to promote narratives where national identities are inextricably connected to their lineage – where the person of the monarch is conveniently presented as a link between the present and the past – the allure of these narratives remains. Like with the placebo effect, knowing the trick doesn’t make you immune to it.

Even a staunch republican such as myself feels so drawn to these narratives that I take a good amount of pride in having memorised the sequence of all kings of Portugal. What’s more, even in the cases where I know little more about the king in question than his name, it feels like knowing this is knowing something significant about the period of these kings’ reigns. Knowing how one king succeeded another feels like knowing how important events are interconnected.

After all, looking at History as a complex amalgamation of actions and agents great and small is too much to ask of any puny human brain. To make sense of History, the use of simplifying narratives is required. The way I see it, there is nothing necessarily wrong with this so long as one doesn’t lose track of the complexity that is hidden beneath convenient stories – especially if one is careful to keep in mind how competing narratives may present complementary viewpoints.

In the case of narratives centred around royal lineages, though typically suffering from the fallacies of great man History, they do provide us with a convenient first lens through which to first look at such large topics as the History of Portugal. Yes, they do perpetuate the tempting illusion that the fate of a “nation” is the result of the wise and ill choices made by great men at their helm, when in reality such men, more often than not, are as unfree in the face of the forces of History as any other; but it really is hard to take a coherent look at long periods of unfamiliar History with no reference to such figures.

I guess the problem is that the title of King has a certain magic about it that makes it easy to forget that the person wearing it is not in fact an omnipotent being able to make decisions independently of all around them. Even though a monarch’s lineage is theoretically what justifies their title, none can retain it for long if their decisions, however wise, alienate those wielding real power under them. In fact, our royal narratives are usually filled with just such kings who dared to know better than their great lords and who pursued their favourite policies with no regard for how they would upset the powers that be. Invariably, the powers that be take good care that such “unwise”, “weak”, and/or “tyrannical” kings be more or less swiftly deposed in favour of a more reasonable relative who knows not to bite more than they can chew. However, at the end of the day, these are still people with more power than most, whose actions often have an undeniably disproportionate impact. After all, it is hard to argue that, e.g., the character of one Henry VIII did not significantly affect the destiny of England, whatever else may have contributed to it.

And even when looking at times when the person sitting on the throne clearly had a very limited impact on the country, it still seems like there is something to this informal version of the Japanese custom of naming eras after emperors: splitting time into eras lasting as long as the reigns of monarchs somehow makes it easier to weave all sorts of stories about how the world changes with each successive generation (it doesn’t even need to be all about that one person!). It’s not even necessarily a disadvantage that these eras don’t all last equally long: after all, a longer reign is usually associated with a more stable period, so that gives you useful information too. Of course this is not a perfect model, but it is certainly useful – so long as you don’t forget that monarchs aren’t literally making the world go round and are just being used as very narrow windows that allow us to peer into their time.

With all of these caveats in mind, I decided to write a series all about giving a very simplified overall view of the History of Portugal (from its origins up to 1910) through very short summaries of (the reigns of) every Portuguese monarch. (Only two were queens, and “king” sounds better than “monarch”, so sorry about the title.)

In what follows, I give you for each monarch: a reigning name and number; a cognomen/epithet (or two, where I find more than one to be sufficiently important); their claim to the throne (usually being the oldest surviving legitimate son of the previous king); either a little-known fact or a quick statement of their claim to fame (depending on whether I deem them to have a claim to fame); the bare minimum information about their consorts; and a few paragraphs about their lives/reigns. For each of our four dynasties there will also be some introductory remarks just to set the historical mood.

Before we jump into it, please allow me just a few additional clarifications about how names are written. Firstly, you’ll find the abbreviation “D.” before each monarch’s name. “D.” stands for “Dom” (or “Dona”, for women) and is an honorific somewhat equivalent to “Lord” (or “Lady”). In Portugal, it is customary to always include this title when mentioning kings, nobles, and even modern bishops, so I’m keeping it. Secondly, I’m writing the names of every king as it is typically written in modern Portuguese History books, i.e., following modern rather than contemporary spelling conventions (so, e.g., “D. Dinis” instead of “D. Denis” even though he himself would have signed the latter). This is because despite my qualms I have used these names for too long (having taken forever to realise this was a thing) and I’m now unable to avoid it. Finally, some kings whose names aren’t repeated won’t be given a number (like D. Dinis) while others will be “the first” (like D. José I). The criterion for this is whatever I intuitively feel is most usual/natural (and which probably boils down to the way the whole thing sounds in Portuguese).

Without further ado, I present to you every king of our first dynasty.

First Dynasty (House of Burgundy)

A cadet branch of the House of Capet, descending from the dukes of Burgundy. It is also known as the Afonsine Dynasty, after our first king.

It conveniently covers the period from Portugal’s foundation until just before the Age of Discovery and the Rennaissance. As such, the main themes seen throughout the various reigns are very similar Portuguese versions of the main themes which dictated the fate of countless European Medieval reigns: military struggles with neighbours (notably “the Moors” to the South and León/Castile to the North and East), power struggles with clergy and nobility, and family struggles with a potential to boil over as civil wars and succession crises.

D. Afonso Henriques, the Conqueror [1143-1185]

Claim to throne: Paid the iron price.

Reason for cognomen: It’s pretty self-explanatory.

Best known for: “Beating his mom”, leading Portugal to independence, and conquering a lot of land from the Moors.

Consort: D. Mafalda of Savoy (daughter of the Count of Savoy)

His father, D. Henrique, the Count of Portucale, died when he was between one and six years old. His mother, D. Teresa of León, remained the ruler of the County and followed a general policy of wresting as much power and authority as possible from the Kingdom of Galicia (ruled by her half-sister Queen Urraca and her nephew Alphonso VII). Had things gone a little better for her, she could very well have been the one to become the first ruler of an independent Kingdom of Portugal. Heck, at a point she was even effectively recognised as Queen of Portugal by Pope Paschal II, although not necessarily as an independent queen (her sister and nephew used the title of Emperor of All Spain, which they claimed to hold authority over all Iberian kingdoms). Alas for her, her alliance with the powerful Galician Count of Traba earned her too many enemies at home, including her son Afonso Henriques, who raised arms against her. Eventually she was defeated at the Battle of São Mamede (1128) and Afonso Henriques became Count.

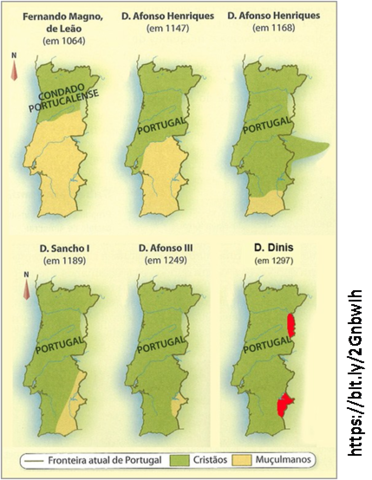

Afonso Henriques clearly never had any intention to remain a subservient vassal, and followed an aggressive military policy whereby he alternated between conquering land from the Moors to the South and rebelling for independence from his cousin’s realm (which were suppressed a few times). Eventually his rebellions became too much for his cousin to handle (he was pretty busy with his own wars against the Moors as well as against the kingdoms of Navarre and Aragon) and he achieved de facto independence with the Treaty of Zamora (1143).

Once his status as King was recognised by his cousin, Afonso focused his military efforts on Southward expansion, and his diplomatic efforts on convincing the Pope to recognise his status as the Pope’s direct vassal (i.e., an independent king, owing allegiance only to God and His vicar). He was largely successful on both fronts (in spite of a particular disaster in 1169 that lost him a good chunk of land around Badajoz, because of course old age didn’t mean he couldn’t personally lead his troops; so he got captured by the King of León and Galicia, then his son-in-law, and forced to give up territory in exchange for his freedom). Portugal’s independence was formally recognised by Pope Alexander III in 1179 and by the end of his reign Portugal controlled almost as much territory as today.

D. Sancho I, the Populator [1185-1211]

Claim to throne: Only surviving legitimate son of D. Afonso Henriques.

Reason for cognomen: After his father conquered so much territory, somebody had to actually populate it.

Little-known fact: His name was originally Martinho, presumably after St. Martin of Tours, on whose feast day he was born; but also potentially indicating he was destined for an ecclesiastical career (besides St. Martin of Tours, Martinho was the name of the saint who converted the Suevi Kingdom of Galicia from Arianism to Chalcedonian Christianity, and thus a popular name among archbishops of Braga). Apparently it was not seen as a name fit for a ruler, since upon the death of his older brother Henrique he became known as Sancho (a popular name for Iberian kings back in the day).

Consort: D. Dulce of Aragon (daughter of the Queen of Aragon)

D. Sancho I comes across as one of those kings who’s pretty boring because he lacks any major flaws. He wisely gave up on squabbling with the kings of León over the Northern border with Galicia, allowing him to focus on fighting the Moors – whom he didn’t blow out of the water but mostly forced to go on the defensive. After his father’s frantic expansion, the main thing that was needed was some stability to effectively occupy and administer the recently conquered territory, and Sancho did just that. He apparently also wrote some poems, but nothing super important as far as I’m aware.

D. Afonso II, the Fat [1211-1223]

Claim to throne: Oldest legitimate son of D. Sancho I.

Reason for cognomen: I don’t think he was very slim.

Little-known fact: He died excommunicated. He was only buried in his final resting place at the Alcobaça Monastery after his successor formally resolved his conflict with the Pope.

Consort: D. Urraca of Castile (daughter of the King of Castile and related to Afonso within the 5th degree of consanguinity)

D. Afonso II was all about strengthening the power of the crown. The militarist policies of his predecessors, though arguably necessary for the establishment of the nascent Kingdom of Portugal, had left a lot of land and power under the control of nobles and military orders. He carried out an extensive revision of the legal status of properties and privileges across the Kingdom to make sure the Crown wasn’t cheated out of any piece of land or income. His reign saw the first recording of Portuguese laws and the first assembling of the cortes (a representative assembly) with representatives of the clergy and the nobility.

D. Afonso II essentially gave military conquest a rest (some Southward expansion did happen, but it seems to have been the result of “private” military campaigns led by the Bishop of Lisbon). Instead, he seems to have fought some internal battles to take control of land bequeathed by his father to his sisters, and to have sent troops to a joint Iberian Crusade against the Moors.

Without a doubt, D. Afonso II’s most important conflict was with the Pope, over his undermining of privileges granted by D. Afonso Henriques to the Church. These grants had been instrumental in getting the Pope to legitimise the rule of the first Portuguese king, but were a significant burden on the Crown at a time when the dynasty’s legitimacy was no longer questioned. D. Afonso II proceeded to spend part of the revenues of the Church on national projects, earning himself an excommunication by Pope Honorius III. He promised the Pope he’d be good and make amends, but forgot to actually do something about it and died excommunicated.

D. Sancho II, the Capuched [1223-1248]

Claim to throne: Oldest legitimate son of D. Afonso II.

Reason for cognomen: I don’t know, actually. It’s a weird one, which seems to refer to a friar’s capuche; but it’s not like he was popular with the clergy at all. Wikipedia claims it’s because he (once?) wore one as a child.

Little-known fact: He seems to have been accused (and absolved) of beating some clergymen with a staff.

Consort: D. Mécia Lopes de Haro (a Leonese noblewoman who was also a great-great-granddaughter of D. Afonso Henriques)

He seems to have wanted to continue pursuing his father’s centralising programme, with disastrous consequences. Even though he started out overseeing a smoothing out of conflicts inherited from D. Afonso II (making peace with the Pope and granting his paternal aunts the lands over which they had fought the old King), he made too many powerful enemies – including the Archbishop of Braga, the most senior prelate in the Iberian Peninsula. Eventually he found himself politically isolated and having to rely on help from Castile to defend himself from his internal enemies. Unsurprisingly, he found himself excommunicated in 1234.

His childless wife was an important target of his enemies (some of whom presumably resented her inner circle being composed mostly of Castilian relations). At the instigation of his brother Afonso, the Pope annulled their marriage on grounds of consanguinity (which, let’s face it, was a valid yet cynical argument in a time when much closer relations routinely wed); yet even then Sancho refused to repudiate her. Later the Pope went as far as to directly call for his deposition in favour of his brother, which he could do little to prevent. In the end he quickly lost control of the realm, had his wife kidnapped, and died in exile in Castile while his brother ruled Portugal (ostensibly as Regent, only calling himself King after Sancho’s death).

D. Afonso III, the Bolounnais [1248-1279]

Claim to throne: Oldest surviving legitimate son of D. Afonso II.

Reason for cognomen: His first wife was the Countess of Boulogne.

Best known for: Having completed the Portuguese Reconquista with the conquest of the Algarve, becoming the first king to use the style of “King of Portugal and the Algarve”. According to popular tradition, the seven castles in the Portuguese flag are meant to represent seven castles he conquered from the Moors – although most likely they are a heraldic reference to his Castilian mother’s lineage (which was added to the coat of arms because rules back then forbade him from using his father’s unaltered arms when inheriting from his brother).

Consorts: Matilda II (Countess of Boulogne), D. Beatriz of Castile (daughter of the King of Castile)

The price for having the support of nobility and clergy against his brother was to swear to let them keep their “traditional privileges”, which he did before returning to the Kingdom to depose D. Sancho II. Notwithstanding, he did benefit the lower classes by protecting merchants, by founding towns, and by summoning the first cortes where peasants were represented. He was also the first king to move the capital of the Kingdom to Lisbon (from Coimbra, which had been viewed as the capital since the days of D. Afonso Henriques).

Having achieved a good measure of internal stability, he managed to complete the Portuguese Reconquista with the capture of Algarve. (There was an understanding between Portugal and León/Castile that each should conquer only Southwards, so as to not have the Christian kingdoms clashing over overlapping interests; therefore after this Portugal could only pursue conquests in North Africa. Despite this understanding, the Emir of the Algarve had sworn fealty to the king of Castile, prompting all subsequent kings of Castile to claim for themselves the title of “King of the Algarve”, which the current Spanish monarch still uses.)

Presumably worried for his succession and eyeing a convenient alliance, upon becoming king Afonso was quick to discard his first wife for a relative of the Castilian King. This repudiation was not recognised by the Church, and thus his oldest son and eventual heir D. Dinis was technically illegitimate at birth. Luckily for everyone, his first wife died soon after, making his second marriage valid and D. Dinis legitimate.

Like his two predecessors, conflicts with the clergy eventually got him excommunicated. Thanks to the support of the cortes (where he’d allowed representatives of very grateful popular classes), he managed to weather the diplomatic fallout and apparently only repented on his death bed – just in time to be forgiven and buried at the Alcobaça Monastery.

D. Dinis, the Farmer [1279-1325]

Claim to throne: Oldest legitimate son of D. Afonso III (at least after the death of his father’s first wife).

Reason for cognomen: He ordered the planting of large extensions of the Pine Forest of Leiria, which was important as a source of wood for vessels used during the Age of Discovery. In fact, he is so associated with this forest that before checking to write this I was convinced he had all of it planted (but actually it may have been started on a smaller scale by his father, or even by his uncle).

Best known for: The Pine Forest of Leiria, being an accomplished poet, making Portuguese the official language, marrying a saint (being the foil in her hagiography), founding the University of Coimbra, and negotiating the treaty that defined (most of) Portugal’s current continental borders – supposedly the oldest in Europe!

Consort: Saint Isabel, the Holy Queen (daughter of the King of Aragon)

Among all Portuguese monarchs, none stands out for diplomatic and cultural reasons quite as magnificently as D. Dinis. Undoubtedly, his reign was the peak of our First Dynasty, and he is a strong contender for the title of Best Portuguese King Ever. Remarkably, he is perhaps the only “A-list” Portuguese king not to be known for military accomplishments!

Right at the start of his reign he could have been in real danger of deposition, as his younger brother had a strong claim to the throne based on Dinis’ illegitimate status at birth. Fortunately for him, his brother didn’t really garner any significant support and ended up exiled in Castile. He also managed to regain a good measure of stability by reaching a long-term agreement that smoothed things out with the Pope, thus ending the streak of excommunicated kings.

The marriage between D. Dinis and Saint Isabel was nothing short of a diplomatic triumph. Isabel’s personal qualities aside (and she is worth a detailed look in her own right), in marrying her meant prevailing over English and French pretenders and securing an extremely valuable ally in the region. (Supposedly as part of the marriage agreement, D. Dinis donated twelve castles and three towns to his new bride, reflecting the importance of the arrangement.) Saint Isabel would go on to become a very popular queen (still fondly regarded today) and to play an important role in keeping the peace at a time of conflict between D. Dinis and his heir, the future D. Afonso IV.

At a point he seems to have been on the brink of war with Castile during a period when the neighbouring kingdom was experiencing internal turmoil. However, at the last minute, he managed to leverage his advantageous position into a recognition of Portugal’s modern land borders (sort of) without the need of an actual military engagement.

D. Dinis was a notorious troubadour and patron of the arts. He seems to have been important at introducing new literary currents from France, and 137 songs of his are known. He made Portuguese the official language in the Kingdom, and he founded the University of Coimbra (originally in Lisbon), the first University in the country and still a major institution.

He also had the Pine Tree Forest of Leiria greatly expanded, presumably to protect Leiria from advancing sand dunes. This forest would become extremely important as a source of wood for vessels used during the Age of Discovery.

The end of his reign was marred by military conflicts with his son and heir, the future D. Afonso IV, ostensibly over (probably unfounded) concerns that D. Dinis might have planned for the succession of his favourite son, the illegitimate D. Afonso Sanches (also an accomplished troubadour).

D. Afonso IV, the Brave [1325-1357]

Claim to throne: Oldest legitimate son of D. Dinis.

Reason for cognomen: His bravery at the Battle of Salado, where a joint Portuguese and Castilian force put an end to the last Moorish invasion of the Peninsula.

Best known for: Being the bad guy in the most famous Portuguese love story.

Consort: D. Beatriz of Castile (daughter of the King of Castile)

The start of his reign was marked by attacks against his bastard brothers, notably his father’s favourite D. Afonso Sanches, who managed to slip to Castile before being declared a traitor and seeing his lands and titles confiscated (another brother, D. João Afonso, was less fortunate and got executed). Following a few years of diplomatic and military conflict, the two ended up signing a peace treaty recognising the King’s sovereignty and restoring his brother’s lands. Apparently this treaty was mediated by the King’s mother, Saint Isabel (who must have been reasonably close with both as she had made a point of having all her husband’s children, by her or others, raised together at court).

He seems to have taken non-insignificant steps towards centralising (mostly judicial) power at the expense of the nobility’s feudal privileges, which is nice. But make no mistake: his approach to kingship was a far cry from his father’s diplomatic touch, as evidenced by his actual wars with Castile (although I guess wars do get you cooler epithets, even if not a more positive coverage in History books). Apparently, Afonso attempted to maintain his father’s policy of keeping good relations with Castile by marrying his eldest daughter to the King of Castile; then got very upset that his son-in-law seemed to openly mistreat his daughter and decided to marry his heir to the daughter of an influential Castilian noble. The King of Castile took offence at that and reacted by abducting Afonso’s daughter-in-law-to-be, triggering a war that was only stopped by the intervention of the Pope and the King of France; just in time for the two kings to be able to make up and ally against the last serious Moorish invasion of Iberia – and for Afonso to take part in the Battle of Salado and earn his cognomen.

All of this is well and good for the relatively brutish standard of Medieval kings, but that is not what D. Afonso IV is known for. What he’s really known for is the part he played in his heir’s tragic love story.

D. Pedro I, the Punisher (the Cruel) [1357-1367]

Claim to throne: Oldest surviving legitimate son of D. Afonso IV.

Reason for cognomen: He was always up for a good old-fashioned Medieval punishing. It is worth noting that his most common epithet, the Punisher, can also be translated as the Justice Maker and has a somewhat more positive ring to it in Portuguese. (The main reason I’ve stuck to Punisher is because we canonically use the same translation for the Marvel character.)

Best known for: Being the good guy in the most famous Portuguese love story.

Consort: probably not D. Inês de Castro posthumously (yes, you read that right)

The story for which D. Pedro is known starts well before he became king, in 1339, when he wed Constança Manuel (the daughter of a leading Castilian magnate) so his father could try to undermine the Castilian King‘s authority. D. Pedro being far from a traditional devoted husband (popular depictions usually portray him as an especially avid philanderer), he soon found himself in an affair with one of his wife’s ladies-in-waiting, D. Inês de Castro, with whom he famously fell in love.

The union of Pedro and Inês was perceived by the old King as not just scandalous but as a political danger. Whilst extramarital affairs were largely par for the course with Medieval nobility, this particular affair had become public enough that it fostered the growth of a Castilian faction at court, headed by Inês’ brothers. In 1344, the King decided to intervene by banishing Inês, who moved just beyond the border to Castile. As legend has it, however, though far from sight, Inês remained ever present on Pedro’s mind, and they kept in touch via letters. One year later, following the death of Pedro’s wife giving birth to the future king D. Fernando, Pedro had Inês return from her exile and resumed their relationship more publicly than ever.

At this point father and son were on an unavoidable collision course. The King insisted Pedro marry again for diplomatic advantage, yet he refused (supposedly claiming grief over his dead wife) and kept things going with Inês; eventually having children with her (two of whom would go on to become serious contenders for the Portuguese throne). At this point all the alarm bells were ringing loud in the King’s mind. He had bitter memories of his own struggle with his illegitimate half-brothers, and he feared the strength of Inês’ children’s claim might motivate attempts on the life of his sickly grandson Fernando. Moreover, as a fractious civil war swept over Castile, more and more Castilian exiles flocked to the Portuguese court, further stoking fears of the Castilian faction’s power. In 1355, the King finally gave up on trying to make his son see reason and gave either the green light or the order for Inês to be assassinated at the Palace of Saint Clare, where she had taken up residence. According to legend, the tears Inês shed as the was killed gave birth to the “Fountain of Tears”, where her blood still taints the stones with a reddish hue (due to red algae).

Pedro’s grief was equal parts loss and wrath. He rose in rebellion against his father (much like his father had once risen against D. Dinis), only to make peace with him after a few months (possibly thanks to the intervention of his mother). But the story doesn’t end with the reconciliation of father and son. Two years later, the King died and D. Pedro ascended to the throne. Now he was in charge and he was out for revenge. Pretty much as soon as he was crowned, he had his lover’s assassins hunted down, and brutally executed the two he managed to capture; reportedly ordering the heart of one to be ripped from his chest and that of the other to be ripped from his back whilst he feasted.

Inês was dead. Pedro’s father was dead. Inês’ assassins had either managed to flee across the border or been violently put to death. Yet legend says Pedro’s vengeance was not complete. Upon his accession, he declared that he had previously wed Inês in secret (thereby legitimising their children) and posthumously declared her Queen of Portugal. Then he had her corpse exhumed and brought to the palace so he could force the entire court to do her homage in a traditional hand-kissing ceremony. (To be clear, this ceremony probably never happened, but it is a legend that has long endured and thanks to which D. Inês de Castro is often referred to as “she who after dead was queen”.) He also made sure that he and Inês ultimately rested in tombs facing each other at the Alcobaça Monastery, supposedly so their faces are the first they each see when they rise on the Day of Judgement.

As King, D. Pedro was a very different from his predecessors, and comes across as mostly uninterested in matters of state except for the serving of justice. And by the serving of justice, I of course mean brutal punishment of perceived wrongdoers, which reportedly included sawing a priest in half for raping a woman and castrating a friend of his (possibly a lover of his) for having an affair with a married woman. And don’t you think for a second he was at least committed to anything resembling fair trials, which he seemed to feel were nothing but a hurdle in the way of the good part (i.e., the punishing); having apparently even gone as far as banning lawyers.

Incredibly, Pedro’s reign ends up being remarkably prosperous, despite his lack of interest in governance. As it turns out, with a civil war ravaging the neighbouring kingdom and in the aftermath of the war against his father, what the country really needed was a period of relative peace and stability. Since Pedro had no interest in making significant changes to how the country worked, or in military expansion, there was no incentive for his nobles to revolt against him (especially as everyone knew the punishment for doing so was unlikely to be light). As a result, peace and stability ensued, and arguably our most brutal king is remembered as one of the most popular.

D. Fernando, the Handsome [1367-1383]

Claim to throne: Oldest surviving legitimate son of D. Pedro I.

Reason for cognomen: If there’s nothing else you can praise in a king, you can always praise his looks!

Best known for: Failing to produce a male heir and marrying his only legitimate daughter to the King of Castile. Oops!

Consort: D. Leonor Teles (niece of the powerful Count of Barcelos, our first queen born in Portugal, and arguably the most hated consort in Portuguese History – due to her role siding with her daughter following the death of D. Fernando)

The story of D. Fernando’s reign is one of disaster after disaster, plus one reform which was kind of OK. The OK reform is known as the Law of Fallows, came in the aftermath of the labour shortages caused by the Black Death and sought to force land owners to put their land to productive use, binding peasants to land for that same purpose. It’s unclear to which extent it was applied, and it wasn’t very nice if you were a farmer’s grandson who didn’t want to be a farmer, but it was innovative in introducing the concept of expropriation. Plus an economic crisis is the only type of crisis we don’t see under Fernando, so let’s let him have this one.

At the beginning of his reign, the illegitimate Enrique de Trastámara became King of Castile after murdering his brother. In light of this, Fernando seemed to fancy himself a valid candidate to be King of Castile, or at least in a good position to weaken the neighbouring kingdom, and embarked on a series of ruinous wars to this effect, intermittently allied to the King of Aragon and to John of Gaunt, the Duke of Lancaster and himself a pretender to the Castilian throne.

D. Fernando’s efforts abroad lacked consistency and were punctuated by unforced diplomatic blunders, including forsaking promises to marry the King of Aragon’s daughter and repeatedly switching allegiances between the Pope in Rome and the Pope in Avignon. Meanwhile, his attempts to consolidate internal affairs were consistently frustrated by discontentment at the influence garnered by his wife’s family. In the end he suffered defeat after defeat and was forced to accept to marry his only legitimate daughter to the King of Castile, thereby endangering the continued independence of Portugal.

In 1383, at the age of 37, D. Fernando died without a male heir, leaving his daughter Beatriz, Queen Consort of Castile, as the natural successor. It was the end of the House of Burgundy in Portugal, and the beginning of a succession crisis which threatened the Kingdom’s independence. The consequences, it turns out, were to forever change the fate of the country…

3 thoughts on “A Brief History of Every King of Portugal: The First Dynasty (House of Burgundy)”